A long time ago, when I was still considering pursuing a path toward teaching as a profession (this consideration was mercifully brief — nothing against teachers but I don’t think I would be a good one), I thought about putting together a syllabus called “Literature and the American Disaster.” This syllabus was going to depend fully on the work’s context, place, and time, all of which I love to talk about. But it also contained the idea of a particularly American response to a cataclysmic event. I never got around to unpacking the concept because frankly, I never needed to finish building a syllabus (and maybe frankly also because I was at my core not super confident talking about Americanness, but fuck it, I got my citizenship last year, let’s fucking goooo).

What makes a disaster American? In my mind, there are a number of factors, and several of them can be true at once. Let’s do a fun list and then you can tell me if I’m missing something.

First of all, I’m considering disaster to mean a calamity that results in widespread destruction and/or loss of life. Most of the time these are immediate events, often natural in origin, but there are also slow-rolling epidemics that we can consider to fit into the category, such as gun violence and (of course) everything around the Covid response in the US.

Qualifications for an American disaster:

It’s made measurably worse by inequality. The disaster at hand is made even more terrible because of racism and wealth disparity; lower-income areas are hit hardest, and receive the least help. This has happened countless times, notably after Hurricane Katrina but also on an ongoing basis, like during the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. There is no need to explain how this factor is tied to Americanness — the wealth gap is higher in the US than any other first-world nation, and it’s grown steadily over the last few decades. Money means everything, including priority, access, and publicity.

It’s politicized. The disaster at hand is immediately made into talking points, and its victims played as pawns — this happens after any act of gun violence. It’s “Thoughts and prayers.” It’s “We have to act! Donate now!” without any real subsequent action. During this year’s DNC, I cried during the gun violence segment, even as I recognized it as politicization: mothers brought onstage to describe the violent deaths of their children. It got me because it was designed to get me, even though I resented the mechanism.

It’s turned into conspiracy theory. The disaster is immediately messaged (by various wing nuts on X or wherever) to be a symptom of some kind of concentrated cabal of power as a way to explain its impact. This happened with 9/11, and it happens regularly with gun violence, and it’s happening now with the current hurricane: “The weather couldn’t do that by itself! Surely this destructive superstorm was the result of weather modification in advance of the election cycle!” Here’s a short piece on the phenomenon.

The official response to it is inadequate for the scale. The disaster is mishandled by a government too bought out by special interests (and too bought in to the idea of American individualism) to be able to react at meaningful scale. Think of any terrible thing, and then think of an anodyne government response to it — once again, gun violence is a great example.

It’s quickly forgotten. Perhaps worst of all: the disaster is just a blip in the public eye, even though the affected community continues to suffer underneath its weight. This is in part because of the rapid news cycle, and in part because the horrors have gotten daily, and it’s hard to grasp them all with equal gravitas. Empathy at scale is exhausting, depleting; this is especially true if it feels like there is never any resolution or recourse. This is systemic failure, not entirely a failure of the individual. We don’t ever get to close the mental loop.

So, given that probably incomplete list, what texts illuminate the way that Americans digest disaster right here at home? There are so many books you could include in a list like that. Their Eyes Were Watching God, certainly. White Noise, with its pervasive fear of death and its unexplained biohazard contaminants, certainly. In recent entries into the genre, there’s Ben Fama’s recent book If I Close My Eyes, which is about a couple of young people who bond over their shared status as victims of a shooting that takes place at a Kim Kardashian book signing. The book is not about guns, but it is — these kids may have low-grade PTSD, but that’s the least of their problems, and this is going to be true for a lot of people growing up with active shooter drills incorporated into the daily routines of their school days.

Anyway, I am not a subject matter expert on disasters, I just wanted to finally list out these things that have existed on the edges of my thinking brain for over a decade. If you’re an educator and you’ve taught something similar, or even if you’re not and you just have a good idea, let me know — I’d love to know what texts you’d include.

One of the books that exemplified this concept for me at the time when I began thinking about this was Blood Dazzler, Patricia Smith’s poetry book about Katrina-era New Orleans.

I remember, in particular, reading the below poem, which is told from the point of view of President George W. Bush during his infamous fly-over of the region:

The President Flies Over

Aloft between heaven and them,

I babble the landscape—what staunch, vicious trees,

what cluttered roads, slow cars. This is my

country as it was gifted me—victimless, vast.

The soundtrack buzzing the air around my ears

continually loops ditties of eagles and oil.

I can’t choose. Every moment I’m awake,

aroused instrumentals channel theme songs,

speaking

what I cannot.

I don’t ever have to come down.

I can stay hooked to heaven,

dictating this blandness.

My flyboys memorize flip and soar.

They’ll never swoop real enough

to resurrect that other country,

won’t ever get close enough to give name

to tonight’s dreams darkening the water.

I understand that somewhere it has rained.

This poem summarizes so much about the distance between the actual disaster and the people in power during it. The beginning: “Aloft between heaven and them” — a solitary line, hovering over the rest of the poem, as if suspended in air. The speaker then notes the most rudimentary of landscapes, with no identifying marks whatsoever: trees and roads and cars. Then: “This is my / country as it was gifted me — victimless, vast” — this line contains both the entitlement of the ruling class (gifted me) and the refusal to see the country as being comprised of people rather than of a monolithic unit. Even if one doesn’t think of US as victimless, it’s still possible to make a generalization of this level every time you make whole-hog statements about a region: Florida is full of crazies. The South deserves what it gets because it votes Republican. And so forth.

Smith then provides the speaker’s internal soundtrack, the pervasive American jingle of “eagles and oil,” a list to which I would certainly add firearms. “I don’t ever have to come down” — he could soar high above forever, letting the echoes of his jingoistic song ring inside his ears, and never look anyone’s suffering in the face. The land would forever remain “victimless” in line with the vision. Just keep flying, boys! We don’t have to look too hard at the details. And then Smith hits us with that last line: “I understand that somewhere it has rained.” The speaker feigns understanding but actually has no idea. He is, however, fine with having no idea. What does the president have to do with the weather?

The book contains many blazing moments; it’s generous in perspective and large in scope. I don’t love “project books” that take a big Something on as a topic in order to seemingly be done with it at the end, and at the hands of a lesser poet this could certainly be a project book. But Smith is a master of her craft. Further, she wrote the book because she perceived, as she mentioned in a 2012 interview, that “there was a danger that Katrina was going to disappear” — the fifth on my list of American disaster qualifications. Smith saw the threat of collective forgetting and it made her keep writing past the threshold of a few poems. I recommend reading Blood Dazzler if you haven’t, especially in this climate.

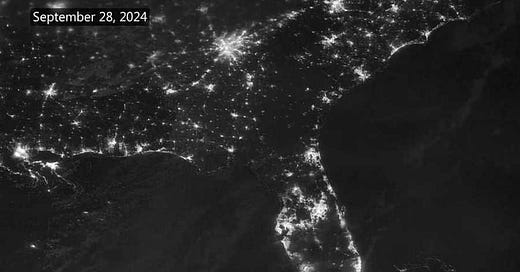

Another reason that I was thinking of this book is that yesterday, President Biden flew over the Asheville area to observe the effects of Hurricane Helene. A storm of terrifying power that intensified quickly after sipping up the warm waters of the Gulf, Helene made landfall in Florida, then swept up to the Carolinas and Tennessee, wreaking havoc in its path. It has completely destroyed the riverfront downtown of my small town, Marshall, North Carolina, as well as countless other riverfront downtowns like Lake Lure, Bat Cave, Chimney Rock, and more. It’s also done extensive damage to Asheville, the largest city in the immediate area, leaving it isolated and without power or cell signal. I have friends who still don’t have power back. There are people in my larger network who are literally missing (the realtor who worked with us when we bought our beloved house, for example). It’s a bad scene here, and I don’t know how much the rest of the country knows about it because I don’t know what the level of wider messaging has been. Biden’s team stated that they didn’t come down from the clouds because they didn’t want to block the one clear path in and out of the region with a motorcade, which, fair. But it’s still depressing to think of this image of a president in the sky, following the path of the fat swath of river mud, and then flying back to the seat of power.

This is by and large not a wealthy region. Asheville makes its money largely on tourism and hospitality — it’s a food town, a beer town, a town for outdoorsing and observing the beauty of nature. Were it any normal year, we’d be entering prime leaf-peeping season. Of course now what we are witnessing is the other side of nature, its terror, and tourists won’t come, nor should they come. But that means that even for uncompromised areas, this storm will have a freezing effect on people’s livelihoods. My house in the hills fared ok — we lost power for a few days, but then we got it back, and we’re on a well so we have water. I’m once again feeling fortunate and trying to funnel resources and money wherever they need to go. So if you’re looking for ways to help and you’re in a position to donate, try any of these:

Beacon of Hope: Organization working to erase food insecurity in Madison County; they’re working to provide food, water, and resources to those affected in the area.

Manna: Food bank serving the greater WNC region.

Feeding the Carolinas: A coalition of nine food banks in North and South Carolina.

Marshall Downtown Association: fundraiser run by locals in my town, with funds to be evenly divided between all the businesses and residents of Downtown Marshall.

Community Housing Coalition: Organization serving housing needs in the area.

And finally — if you’d like to listen to something good while you’re thinking about all this stuff, this week I revisited Rasputina’s 2008 album Oh Perilous World.

Rasputina is the cello-forward project of Melora Creager and her various musical accompanists (on this album, Jonathon TeBeest and Sarah Bowman). You might remember them for their gothy-leaning period outfits, or for their one-time association with Marilyn Manson. I feel like sometimes they were written off a little bit because some of their fans were, like, nerds with low ponytails and shirts that said “Can’t Sleep Clowns Will Eat Me.” But the project is fascinating — Creager is so technically skilled as a musician, and such an interesting vocalist, and each of their albums is ambitious in a weird way, taking on a different era in time.

But Perilous is the first one that takes on the modern world as a subject. Said Creager in 2007: "I wrote the songs[…] over the last two years when I realized that current world events were more bizarre than anything I could scrounge up from the distant past. I obsessively read daily news on the Internet and copied words, phrases and whole stories that especially intrigued me and compiled a vast notebook of this material." The album combines Bush-era politics with the story of the 1790 mutineers who took over Pitcairn Island. The result is an alternate universe of surveillance, tyranny, resistance, and WMDs — surprisingly cohesive and contemporary. Weird as it is, this album holds up. One song asks us to consider: “What will you do when they come for you in the draconian crackdown?” WHAT INDEED. The album also includes tunes about climate change, and pandemics, and superstorms. I highly recommend the duo of “A Retinue of Moons/The Infidel Is Me.”

Anyway, if you made it this far, thanks for reading, I love you.